Rapid and Reactive Healthcare Design for COVID-19

The healthcare community has been preparing and practicing for catastrophic events since 9/11. From the early 2000s on, emergency departments have refined protocols for threats to public safety that reflect what we see today, such as intake nurses’ desks encased in glass to prevent the spread of anything potentially infectious. Despite what we sometimes hear, the American healthcare system is well equipped to care for all of us throughout the natural courses of our life cycle, from birth to death with the inevitable illnesses that befall us between. But pandemics only occur on average every 100 years, and the world is facing a new type of disease with COVID-19. What the conditions of this novel Coronavirus have created are more akin to a biochemical threat than a military or terrorist threat. It has created a tidal wave of demand that isn’t a shortage of beds but an increased demand for a very specific type of care – and various stages of care along that spectrum.

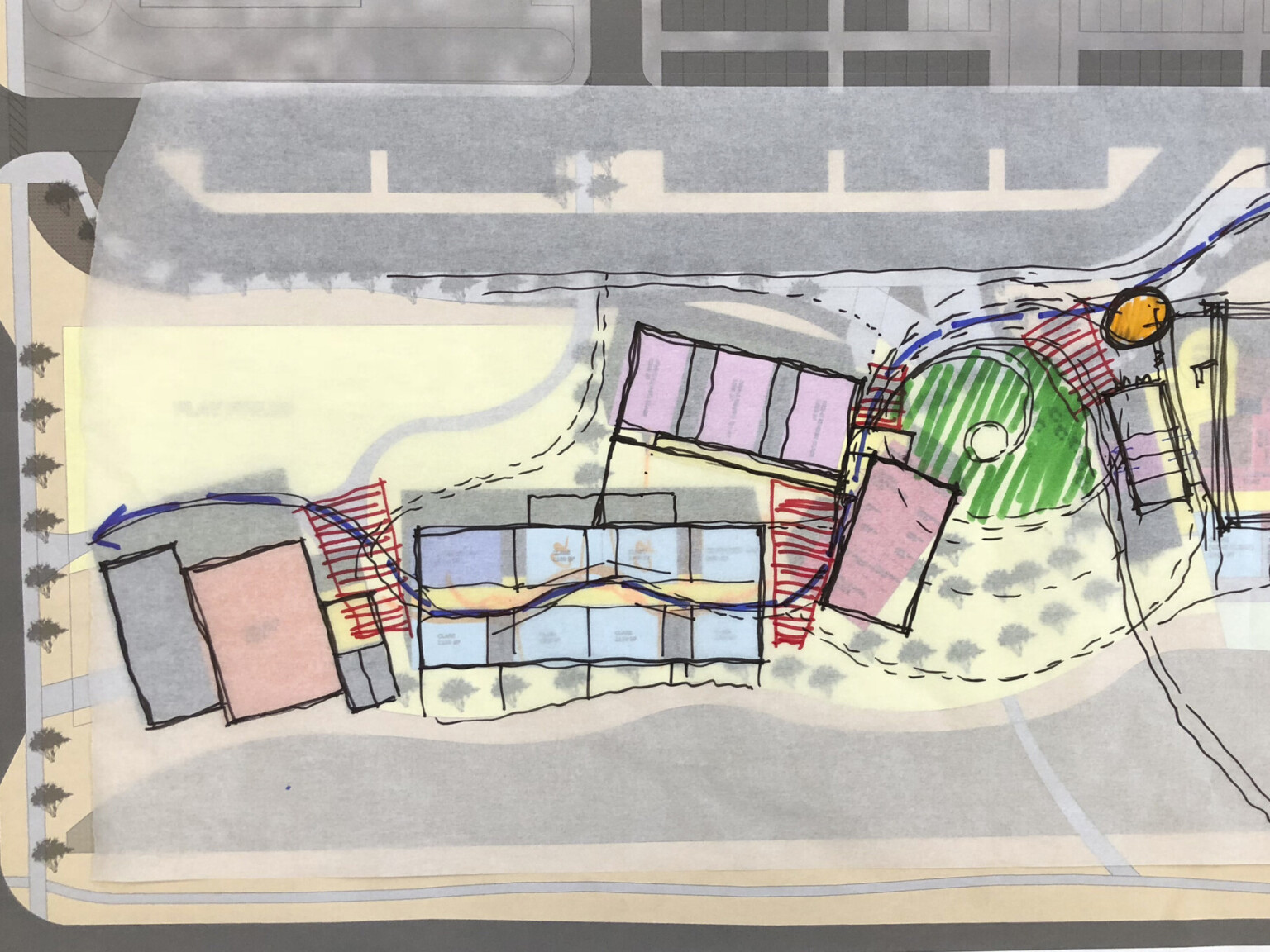

For healthcare designers, architects, engineers, and planners, the exercise of designing any facility must always begin with defining the environment of care. This establishes the goal of the endeavor in a more specific – and therefor more achievable – way than “save the lives of people who have tested positive for COVID-19.” For King County, we had to identify a system of conditional reasoning and logical equivalence very quickly for a specific user group – the homeless population – to ensure this vulnerable cohort was isolated and protected. In retrospect, this sounds very simple. But planning a physical environment to support a coordinated medical response amidst a pandemic outbreak without a clear grasp of the virus we’re fighting proved to be the first hurdle. We had to first understand the disease.

First, the patient had to be tested for the virus. If those who tested proved negative for COVID-19, they were released from the testing facility with directions to stay away from others to remain healthy. If the test results were positive, the patient was then quarantined to prevent the spread of the disease to others. And they need the right type of environment in which to recover.

Second, the level of acuity must be identified to establish the environment of care. While many recover at home, the virus affects others more seriously and requires hospitalization. Some research shows it can trigger a block of oxygen to vital organs, and we know those with comorbidities are at an increased risk. The latter group is where the bottleneck to the healthcare system is occurring. These vulnerabilities, coupled with the rapid spread of this disease makes the extreme demand for specialized environments of care a unique design challenge under current time constraints. Depending on acuity, various features such as hookups for vacuums and gasses, plus infrastructure and square footage to accommodate those features are all critical pieces to a rapid resolution.

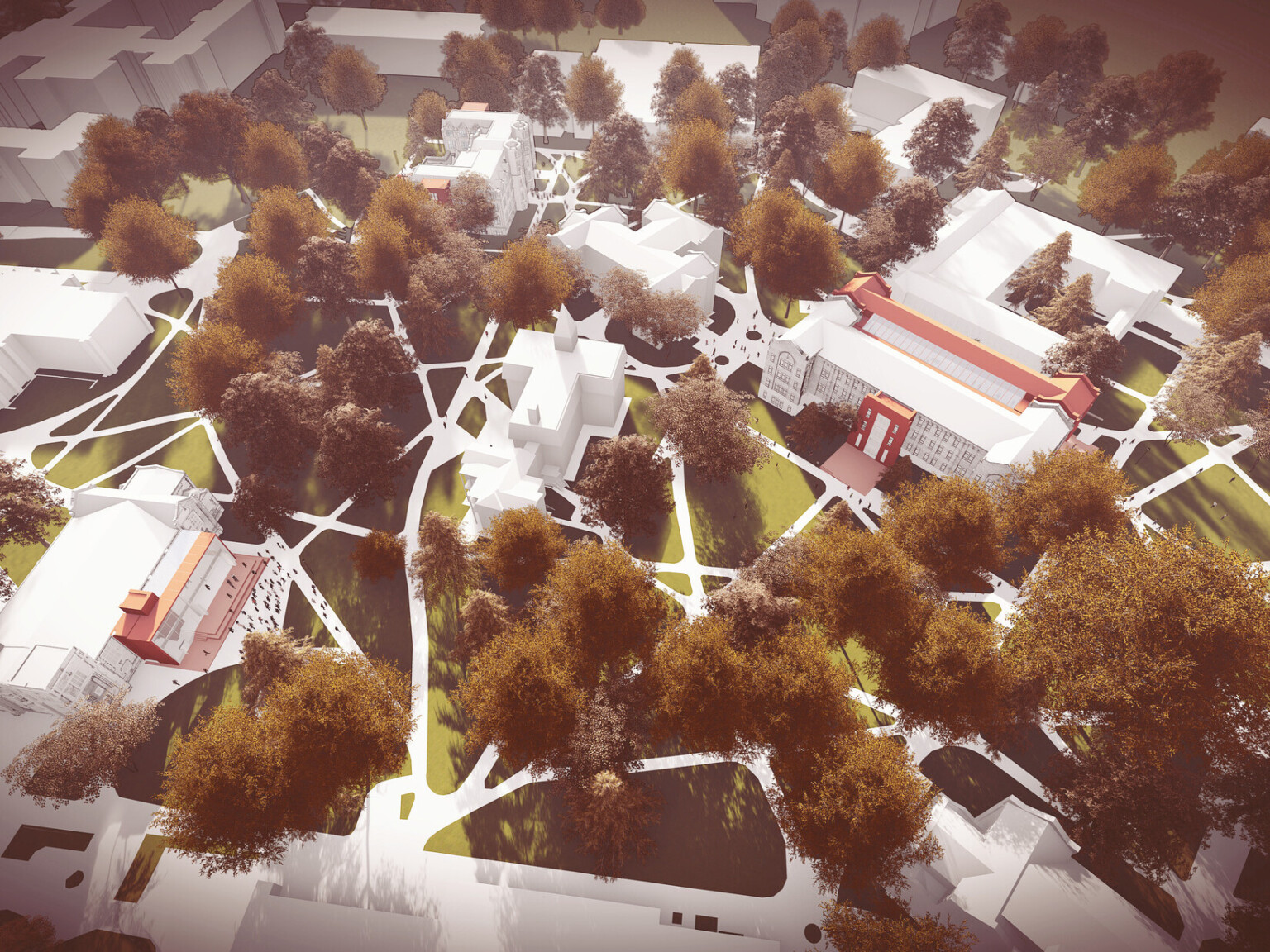

Third, we most often have an anticipated length of stay in a typical patient model. In King County, Washington, we designed and delivered environments of care for those who had tested positive for the disease but did not require hospitalization. From converted motels and warehouse to temporary structures erected on parking lots and athletic fields in and around Seattle, we’ve designed and planned 2,500 beds across 12 sites for patients who are incapable of self-quarantine. These recovery centers are not traditional hospitals but do utilize planning protocols to move patients and staff through the centers in order to restrict the spread of the virus, as we would in any healthcare environment.

Finally, if you’re considering the adaptive reuse of an existing structure, make sure your building team is effectively evaluating your site for viable conversion. We have many inner city and rural hospitals across America that have closed; but getting the infrastructural systems up-to-date for safe operation could take more time than converting a newer building that was originally designed for a different purpose. If you’re hedging bets against a hospital or a motel, it is totally site dependent.