The Global Impact of Resilient Research Communities

Dr. Francis Crick famously opined that “the problem with scientists is that they work too hard, and what they don’t do is think enough.” As the pandemic continues to cause disruptions professionally and personally, institutions around the globe are recognizing the significance of deep thinking to develop alternate scenarios, evaluate risk, practice resiliency, and implement strategies for a sustainable future.

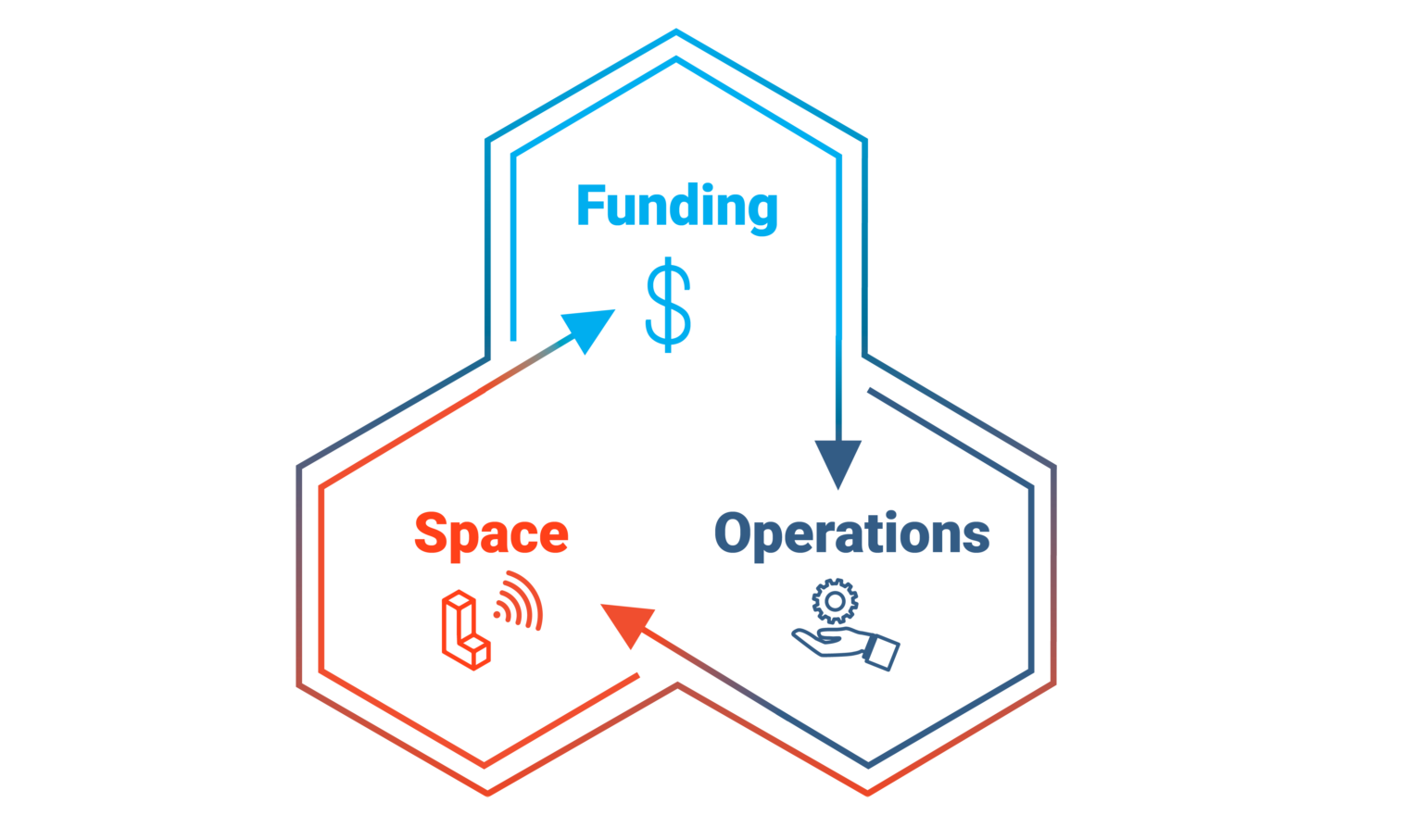

With the recent closing of research campuses, the anticipated budget shortfalls from multiple revenue streams suggest that the ongoing crisis will hamstring institutions financially for years to come. Considering the impact of research dollars on any campus or economy, there is a compelling argument for both reflecting on scientific research’s potential and how best to support its advancement financially, operationally, and physically.

Funding

Universities, institutions, and government funding agencies are reconsidering practices, policies, and funding structures for ongoing and new research endeavors. They are exploring deeper funding for research and stronger workforce preparation initiatives that could signal opportunities for public health and research campuses to pool their resources and energize their thinking. While certain exemptions exist for accessing facilities to maintain equipment, preserve essential experiments, or protect animal populations, a majority of research projects have been postponed or cancelled. These delays are requiring researchers to work closely with funding agencies to develop guidelines and clarify what work can continue off campus.

Operations

Campuses nationwide have been hard at work creating transition plans and guiding principles for reopening their research labs. They are rethinking operational protocols such as split shifts, strict training on accepted practices prior to reentry, reinforcing a culture of safety, remote working whenever possible, and reinforcing time-tested universal precautions that have been in place since the 1980s. The pandemic presents an opportunity for research networks to expand and evolve through new avenues of inquiry – and new evaluations of how labs might operate in the future. The shutdowns emphasize just how critical group connectivity is, even while working remotely, and have highlighted the diverse ways research teams are executing work. Open-source models are being developed and improved to create a common knowledge base that researchers can more quickly and affordably develop responses to research questions. However, the Internet of Things will be more pressured to – at the same time – support legacy research and equipment as well as advance current operations.

Space

As research spaces reopen, scientists are doing so with some anxiety. At least in the short term, team cohesion is threatened as adjunct positions and students learning from home will not be available as lab techs and aids. The pandemic has changed how lab design should respond to technology and innovation. Perhaps spaces located in diverse locations could be planned and designed in collaboration. Spaces shouldn’t be fixed with permanent infrastructure, but rather start out like the skunkworks of older generations. You may recall, Hewlett Packard started in a garage.

While in-person and one-on-one meetings may be temporarily discouraged, flexible collaboration spaces for general use should continue to be strategically located at circulation nodes. This will allow for distance conferencing between research communities/buildings to be set up to focus on the sharing of knowledge and ideation. With the burgeoning acceptance and development of technology and teleconferencing apps, research communities can revive their research and move towards a safer, risk mitigated, and more resilient future. Plexiglas workstation shields will only be a temporary design hack solution because working in a lab is, by definition, a hazardous work environment.

Restoring Research Communities on Campus

The speed with which labs and campuses shut down in response to COVID-19 left little time for researchers to plan for the implications of, or potential opportunities for, continuing their work remotely. However, the work continued. Research communities improvised on their kitchen tables, and converted spare bedrooms or garages to learn, publish, devise experiments, and to share expertise. According to Sciencemag.org, the COVID-19 literature published since January has reached more than 23,000 papers and is doubling every 20 days — among the biggest explosions of scientific literature ever.

To ramp up safely and to forestall future crises, more planning and better planning is needed to evaluate risk, test fit alternatives, and inform decision making that will synthesize both public health concerns and the critical need for research to continue. Since so much of laboratory operations is and will continue to be instrument based, institutions can look at a much different work environment landscape that stresses change will happen; they can plan for it, expect it, and embrace it.

Across the world, this time period has highlighted both the results of collective action and polarization. The global research community has drawn on its passion to embrace both the big idea and tackle the challenging work of building sustaining alliances and finding novel ways to work that uncover answers to society’s most troubling and compelling crises.

This narrative was completed as part of The Evolution of Campus research project and authored in partnership with Vicki David and Krisan Osterby.