Reinventing the Academic Library

Libraries are traditionally located in the central core as the quintessential heart of the campus. They are owned by none yet used by all. While the purpose of the library remains relatively consistent – to serve all campus constituents – the physical design and use of the space continues to evolve.

Physical collections drove the design of library facilities for centuries, resulting in multiple levels of stacks of books readily available for users to peruse or check out. Chairs and study tables were sprinkled throughout the stacks, but the space was predominantly filled with printed volumes. It’s this once-coveted book space that now offers the opportunity for the academic library to reinvent itself.

Rethinking the Midcentury Modern Design Model

Throughout my career, I’ve been fortunate to lead the planning and design of multiple academic library renovations or new builds. These projects have led me to explore library facilities on campuses across the country, and I’ve found that Midcentury libraries – or those with approximately 50-to-80 years of use – are prime targets for renewal for many reasons.

Older libraries are introverted. They are not porous. They typically feature one entrance/exit, which is a solution used to protect the collection and reduce the number of lost books. Libraries designed in this manner miss the opportunities for collaborative space crucial in learning today. To remedy these challenges, an influx of institutions with decades-old libraries are making sweeping changes. Understanding their physical collections by evaluating what’s currently in circulation helps to determine the amount of potential space available to transform the facility into a future-facing environment focused on generating knowledge versus storing it.

Understanding User Expectations

I remember going to the library as a student. Food and drink were explicitly prohibited and talking was frowned upon. Thankfully those rules have changed over the years, as institutional leaders recognize the need to nourish while studying, and converse while learning. Walk into an academic library on any given day and you’ll find meals, snacks, drinks, and conversations everywhere. This trend isn’t going away and must be considered in the planning of a re-imagined library. Most libraries can be organized from lively to quiet to encourage collaboration, as well as to accommodate contemplation. Placing nourishment near an entry also entices potential non-users into the building and offers them a glimpse of a space they may not have considered personally useful.

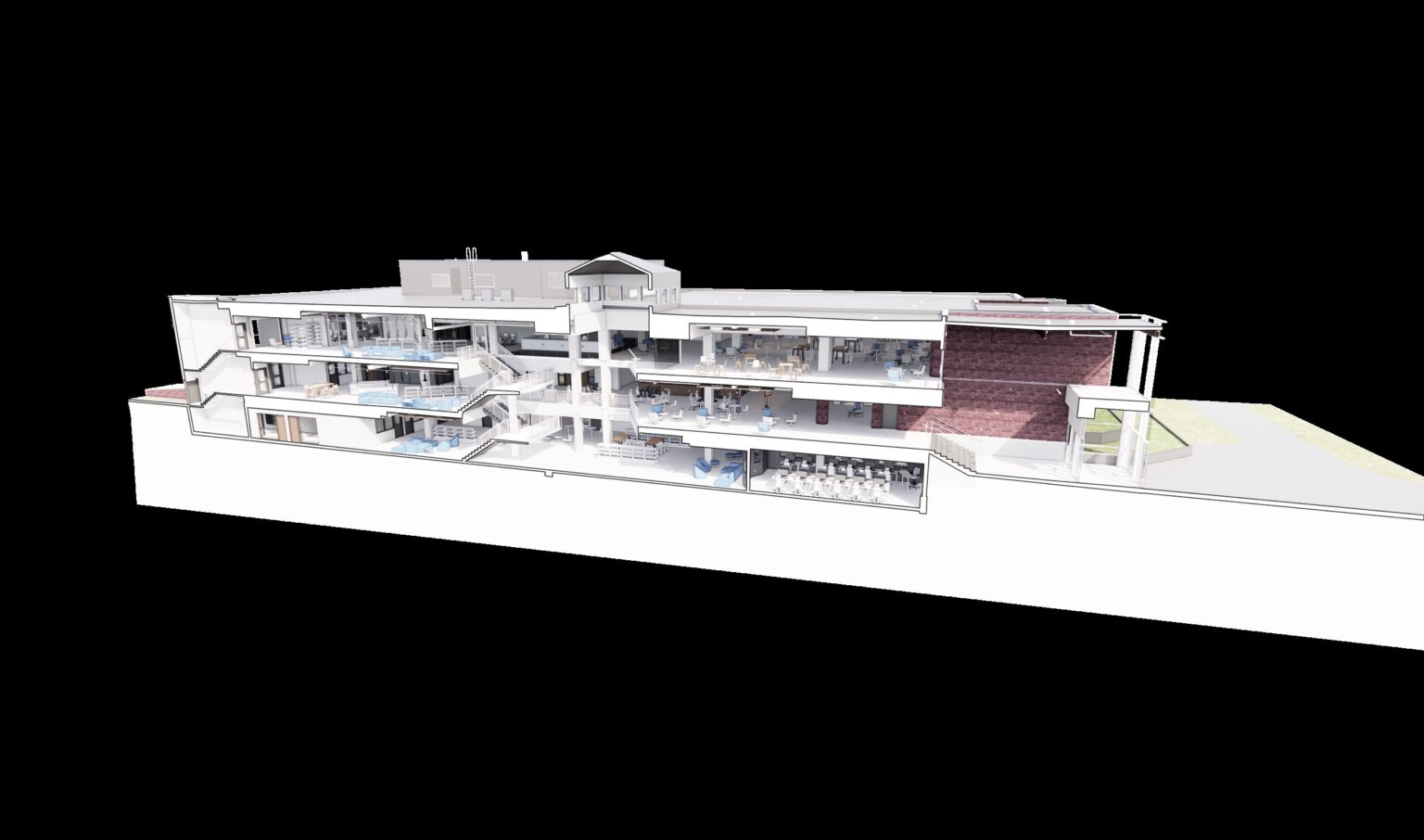

Yes, the acceptance of food, drink, and conversation has changed over time, however, in this era of high anxiety, the expectation for quiet study zones in libraries remains intact. To appropriately accommodate both active and tranquil needs, today’s libraries are designed with noisy areas near the entries and along the main circulation pathways. Quiet zones are strategically placed on upper levels or on the periphery to support individual study time.

In addition to offering spatial variety, ubiquitous technology also defines a modern library. Access to power is in high demand, especially for students who spend their day traveling from building to building on campus. Ensuring adequate infrastructure and a well-planned power backbone ensures the success of any library renovation that will withstand advancements in technology over time.

Design and Planning Opportunities

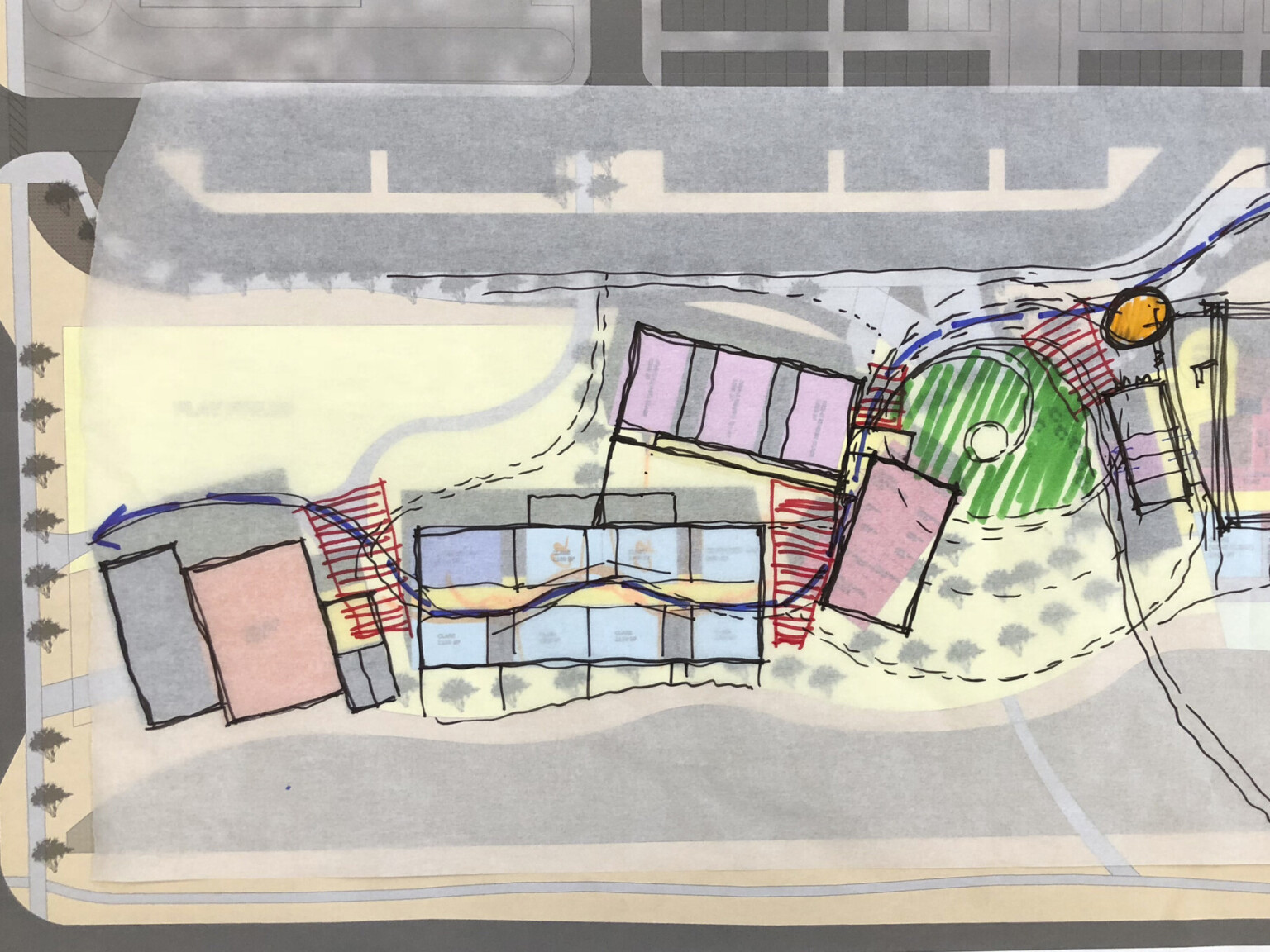

Modern libraries are porous and serve multiple functions, from the learning commons to group gatherings to individual work. They contain multiple entry and exit points to encourage walk-ins from all directions. And they connect the inside to outside elements of nature, through expansive views or designated outdoor spaces like patios, decks, or gardens.

Wayfinding also plays an important role in library design. Reimagined libraries are more than stacks of books and reading nooks; they offer a variety of programmatic space types that may be unfamiliar to first-time visitors. These users must be able to intuitively navigate through digital means such as interactive boards that display available spaces, or through static signage to direct people to their destination within the building.

Adding a vertical component or a double-story grand connection within the library creates a people-friendly environment and naturally draws energy into the building. Midcentury libraries featured compressed one-story stack spaces, which felt uncomfortable and undesirable as people space. Retrofitting these facilities from book space to people space can be as simple as carving out old book stacks, adding double-height spaces, and introducing daylight.

Libraries can also serve as spaces to fill programmatic or service gaps that may exist on campus. For example, library facilities provide the opportunity to connect the dots by offering smaller-scale programs such as maker spaces, AR/VR/AI labs, or editing and recording studios to allow students to try something new before transitioning to a more robust offering elsewhere on campus. They are also natural spaces to infuse student engagement and well-being. The way new or existing space is optimized can create opportunities for this desired engagement.

As core collections transition from physical to digital, special collections expand as a differentiator for many institutions. Special collections, such as artifacts and traveling exhibits, often drive infrastructure decisions. Most of these collections have specific mechanical and electrical system requirements for relative humidity and temperature beyond what’s currently in place in an older library building. Updated systems must be considered to protect and preserve these priceless pieces.

The Next Chapter

A library is the heart and soul of a campus. And as designers, it’s our responsibility to embrace a library’s history, respect its past, and seamlessly create an environment that will serve student populations for the next 100 years. The evolution of the academic library transforms a house of books where people consumed information into a vibrant environment where people gather to generate knowledge.